History of the Milwaukee Astronomical Society

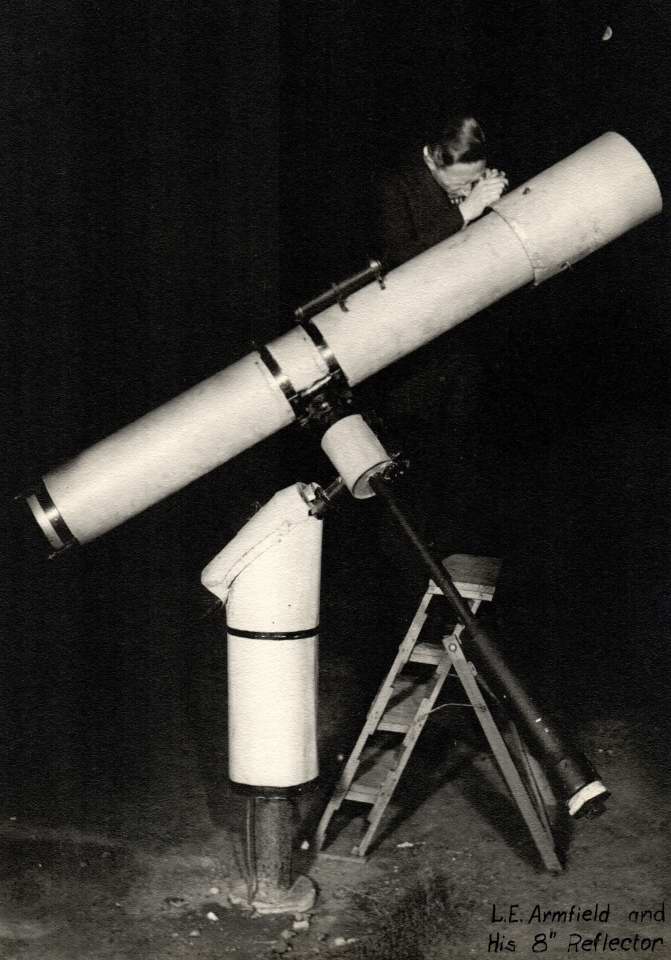

1927-1932 - Luverne Armfield and Friends

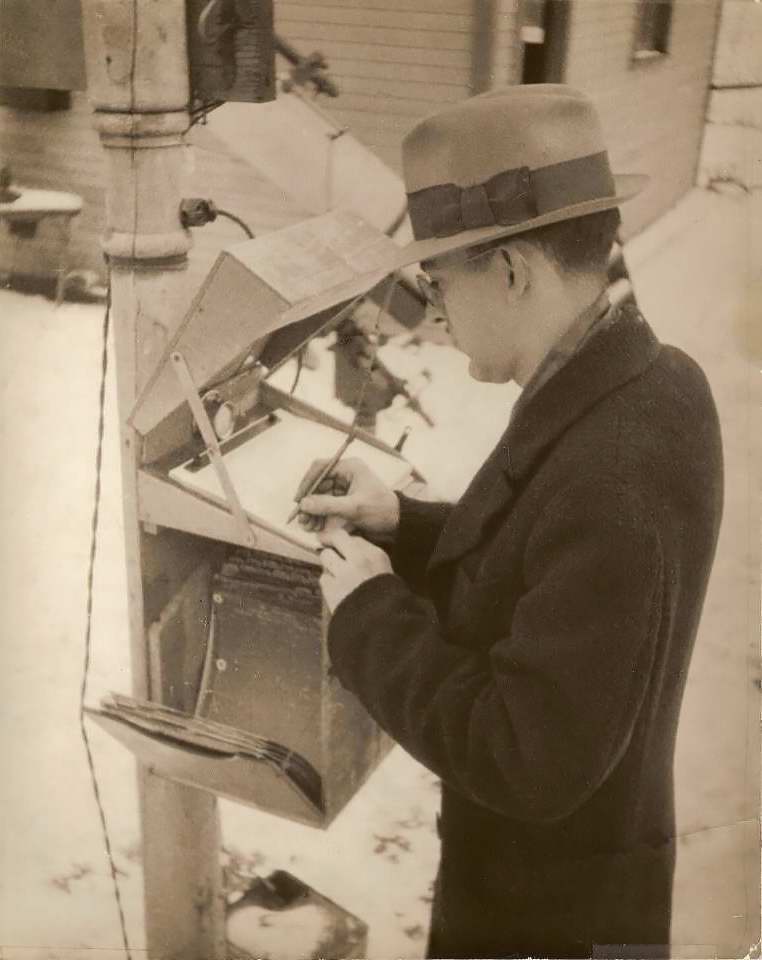

By 1931 he started observing variable stars, an endeavor which allowed amateurs to contribute to the science of astronomy. He did that through the American Association of Variable Star Observers (AAVSO). Armfield also became an avid observer of meteors, both doing counts and then trail plotting.

Along the way Armfield met other amateur astronomers who were regularly invited to observe from his backyard.

1932-33: Formation of MAS / Backyard Observatory / Land Offer

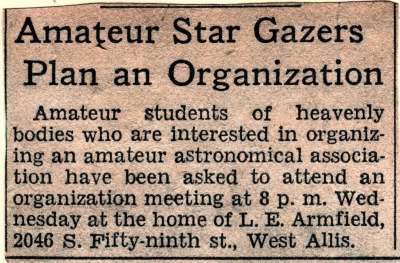

By early September of 1932 Armfield and his friends decided there might be enough interest in the Milwaukee area

to organize an astronomy club. Armfield purchased

the following ad which appeared on page 5 of the Milwaukee Journal of Sunday, September 18, 1932:

By early September of 1932 Armfield and his friends decided there might be enough interest in the Milwaukee area

to organize an astronomy club. Armfield purchased

the following ad which appeared on page 5 of the Milwaukee Journal of Sunday, September 18, 1932:

"Amateur Star Gazers Plan an Organization. Amateur students of heavenly bodies who are interested in organizing an amateur astronomical association have been asked to attend an organization meeting at 8 p.m. Wednesday at the home of L.E. Armfield. 2046 S. 59th St., West Allis"

The meeting went well and the Milwaukee Astronomical Society was formed as a result. There were 18 charter members. The chairman of the group was Edwin Arthur de la Rulle who will become the first President. Elizabeth Wight was elected the Secretary and Treasurer. The dues were $1.00.

The newly formed group began regular observing sessions in Luverne Armfield's backyard which they called "Star Parties." Though they had a decent collection of their own telescopes, they had no outstanding instruments, and, of course, they were observing from within Milwaukee. From the very beginning there was an emphasis in doing scientifically valuable observing. Armfield was one of the earliest observers for the American Association of Variable Star Observers (AAVSO - Armfield's observer code was "A") and an observer of meteors. He would get many new members to give these observing programs a try.

The other big interest of the newly formed club was telescope making. Not only were commercial telescopes practically nonexistent, they were also completely unaffordable. Therefore, a big attraction of the club was to get help in making instruments. And, fortunately, the club attracted a good group of experienced telescope makers willing to lend a hand. Armfield's basement was used as a place for mirror grinding and telescope construction.

By the end of 1933, the membership swelled to 130: 100 regular members plus 30 in the junior auxiliary, which was a subgroup of members who were not yet 18 years old. Local interest in astronomy soared and a good measure was the Milwaukee Public Library's section on astronomy increased by eight-fold. The number of telescopes owned by members expanded to 60. The members continued their observations of variables, as well expanding the scope of the meteor work by making height calculations. These observations were reduced by hand and sent to Flower and Cook Observatory in Upper Darby, Pennsylvania.

In 1933 there was particularly great interest in meteors as the Leonid meteor shower was due to have its 33 year peak. Armfield organized groups of members to observe the event at various locations. Unfortunately, the expected meteor storm never materialized, either unobserved because of clouds or it just didn't generate the expected high meteor count.

With the swelling membership, it was getting pretty crowded in Armfield's backyard so it is hardly surprising there was talk about the dream of securing land outside Milwaukee and establishing an observatory. But incredibly, for the first several months of the club's existence there wasn't a single person who spoke aloud about the possibility. The reason: fear of ridicule!

The reason was they were in the middle of the Great Depression. Unemployment at 25%, many lost their savings in one of the many bank runs, and deflation. On its surface, deflation doesn't sound all that bad, but it is. Why buy anything when it will probably be cheaper tomorrow? And, also, of those who were still fortunate enough to have jobs, got pay cuts. So the reality of some remote observatory was a distant dream which they called their "Castle in the Air." But they dreamed nonetheless and did what clubs tend to do: they formed a committee. They went as far as drawing up plans which included building a 16 inch reflector and then persued an idea of putting the observatory in a public park so they could get city funding for the construction. But there was simply no money available. However, there will be a silver lining to this reality and will embed itself into the DNA of the club. The economics will be a very powerful incentive for people to work together for the common goal of building and maintaining an observatory.

Group picture in Armfield's backyard for the visit of Dr. Harlow Shapley. Walter Scott Houston is posing with the child. Click here for a key to the picturel

One of the very early members was Walter Scott Houston who would go on to some fame as a writer for Sky & Telescope. (In the picture at the right, he is in front with the child.) Another early member was William (Bill) Albrecht who joined when he was still in high school and remained a member until his death in 2009 at age 91 - 76 years.

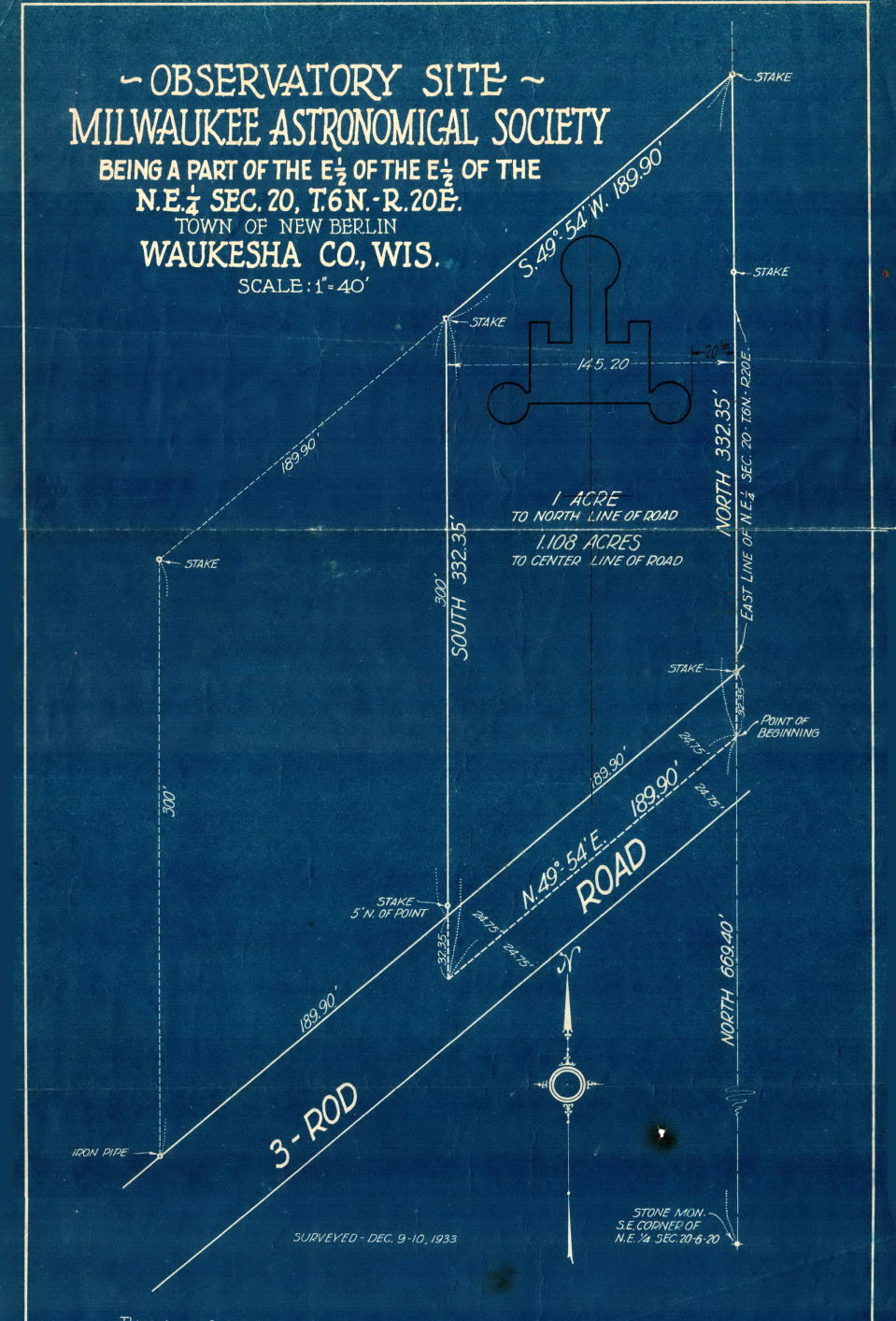

Land Offer

In early December of 1933, the establishment of a real observatory suddenly became a real possibility because of an offer of land to the MAS. A member, Professor M.J.W. (Matthias Jacob Washington, known to friends as Matthew) Phillips, a high school science teacher at West Allis High School, offered an acre of land from his family farm in Waukesha County, which at that time was just outside the town of New Berlin. The story is Prof. Phillips wasn't sure it was a suitable site, but a quick trip by the stunned board and observatory committee immediately made the trek to the site and what they found was better than their wildest imaginations. The site was deemed nearly perfect.

The

land was on a hilltop with great horizons in all directions as it sat in the middle of the Phillips farm.

It was 960 feet in elevation which is almost 400 feet above Lake Michigan. It was close to a good highway

(now known as National Avenue), but not too close. And it was off a good

quiet road: 3-Rod Road which one day

would be renamed Observatory Road. And then there was the Goldie Locks feature of the property: it was

15 miles away from Milwaukee. Far enough away from the city to be very dark, but still not too far away

as to be inaccessible by most of the membership.

The

land was on a hilltop with great horizons in all directions as it sat in the middle of the Phillips farm.

It was 960 feet in elevation which is almost 400 feet above Lake Michigan. It was close to a good highway

(now known as National Avenue), but not too close. And it was off a good

quiet road: 3-Rod Road which one day

would be renamed Observatory Road. And then there was the Goldie Locks feature of the property: it was

15 miles away from Milwaukee. Far enough away from the city to be very dark, but still not too far away

as to be inaccessible by most of the membership.

On December 9-10, Frank Dieter who was the head of the committee and a professional surveyor, made an official plat map of the site which is displayed at the right. As you can see, the name of the road at that time was 3-Rod Rd which will one day become Observatory Road.

But Phillips had two important stipulations. The first was the land and observatory would go to Carroll College should the society cease to exist or the land was no longer being used for astronomy. At the time this seemed reasonable. But he had another stipulation that could kill the offering: construction would need to begin within 5 years. Why? It is important to keep in mind that they were in the middle of the great depression and at the time Phillips made his offer, the club had only been in existence for just 15 months! So it was far from certain at that point the club would continue and in the short term, get enough money and member enthusiasm for the monumental task of constructing an observatory. And it is clear that Phillips was donating this for only one reason: he wanted the site to be used as an observatory. But there was no good reason to decline the offer and it was gladly accepted, albeit a tentative one because we could not take possession of the land without a working observatory.