History of the Milwaukee Astronomical Society

1934-35: MAS Incorporates / 13-inch Telescope / AAAA

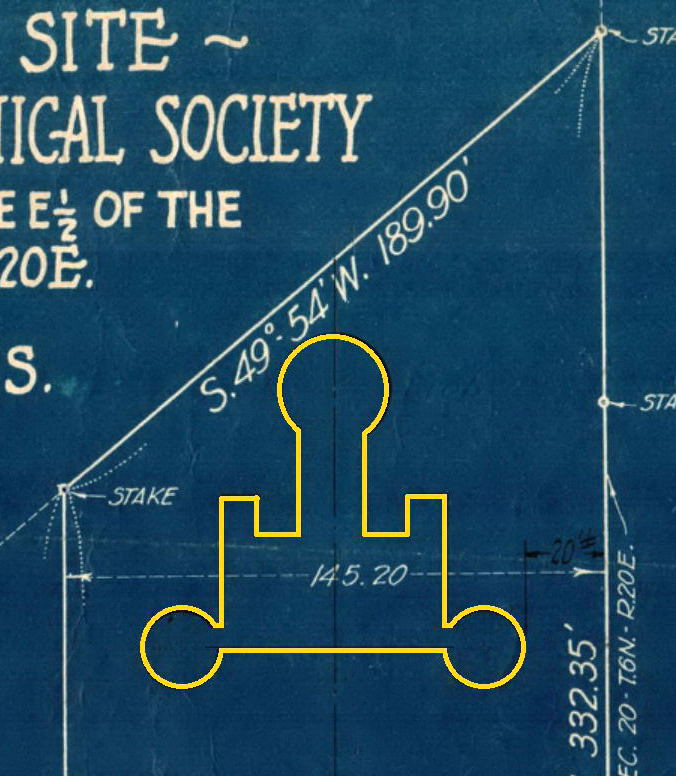

The committee, headed by Frank Dieter,

made another trek to the site on January 28, 1934, this time doing a quick survey. The

topographic map that was made as a result of the survey showed there was an available

tract of land 190 feet in length and 70 feet in width, practically level, located at the summit of a ridge

running diagonally across the observatory site. The committee then

drew up plans for a 14 foot domed observatory which could

accommodate up to a 16 inch telescope (designed by Ray Cooke), with another identical observatory some 50 feet away to be

built later. Then the two buildings would be joined, providing a meeting area. Finally, a third larger dome could be built

later to the north accommodating a 24-30 inch telescope.

The committee, headed by Frank Dieter,

made another trek to the site on January 28, 1934, this time doing a quick survey. The

topographic map that was made as a result of the survey showed there was an available

tract of land 190 feet in length and 70 feet in width, practically level, located at the summit of a ridge

running diagonally across the observatory site. The committee then

drew up plans for a 14 foot domed observatory which could

accommodate up to a 16 inch telescope (designed by Ray Cooke), with another identical observatory some 50 feet away to be

built later. Then the two buildings would be joined, providing a meeting area. Finally, a third larger dome could be built

later to the north accommodating a 24-30 inch telescope.

At the right is a basic rendering of that concept which was hand drawn onto the plat map prepared by Frank Dieter. It was marked in black, but here we have changed the color so it's more apparent. Cooke made a model of the proposed telescope and observatory which is seen here on the left. But with no funds, the plans would be shelved for several years.

In February of 1934, the club established a newsletter called the MAS Bulletin

which would be

published until December of 1935.

You can read those issues here.

The monthly meetings were held at the University of Wisconsin Extension

Building on 5th and State.

which would be

published until December of 1935.

You can read those issues here.

The monthly meetings were held at the University of Wisconsin Extension

Building on 5th and State.

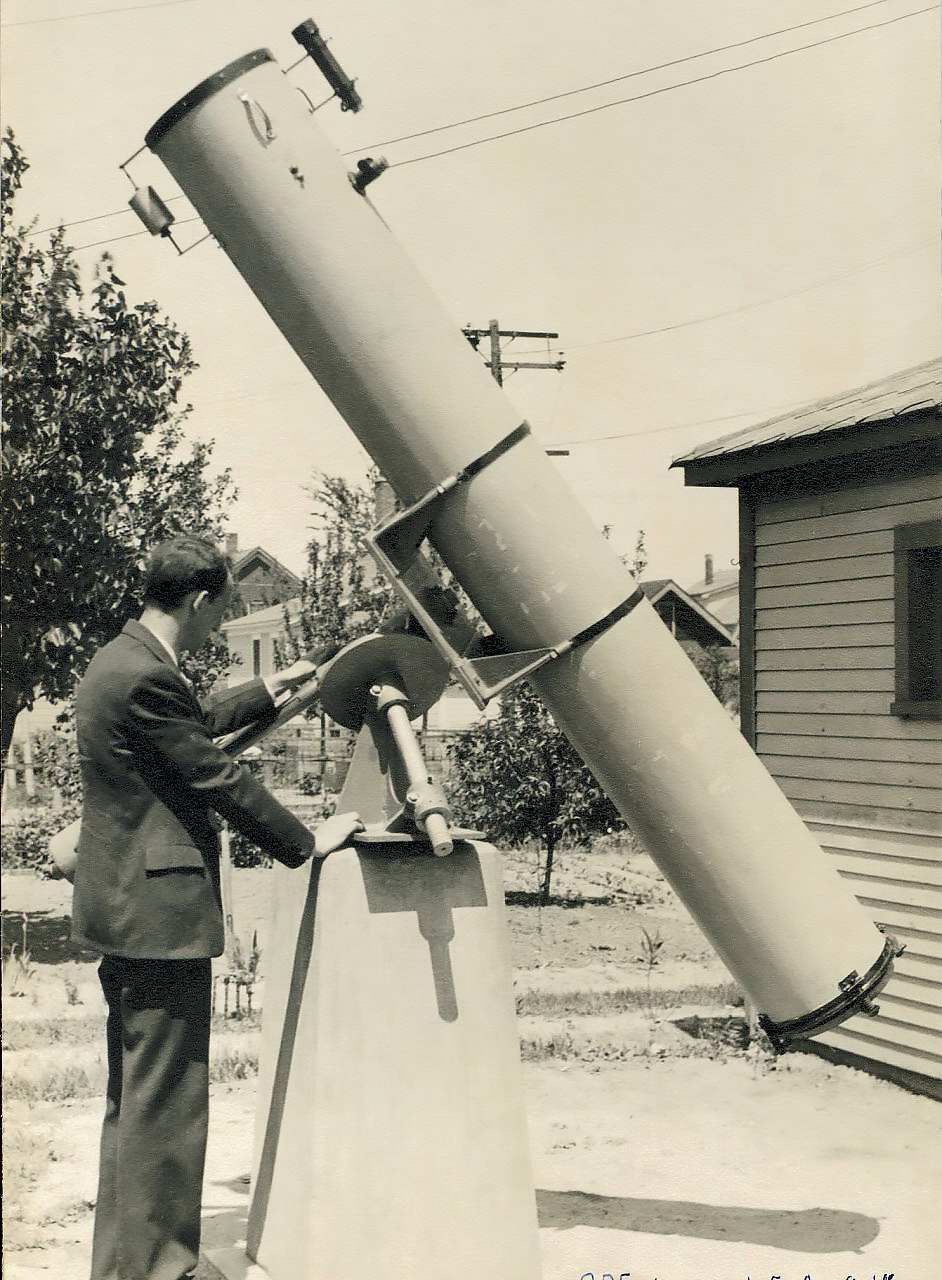

Also in February, Luverne Armfield, in recognition of both his variable star observing and the number of new observers he'd recruited through the MAS, was offered the use of a 13-inch plate glass mirror from the AAVSO via Harvard College. It was made with the understanding that he and the society could have it as long as they pursued the study of variable stars. It had a focal length of 102.5 inches making it an f/7.88. Immediately Armfield and other members got started with fashioning a telescope and mount which was largely funded by Armfield. Arthur Fotsch designed the German Mount and Charles Fischer of the Koehring Company built it.

You can read about the entire history of this telescope (now known as the A-Scope) here.

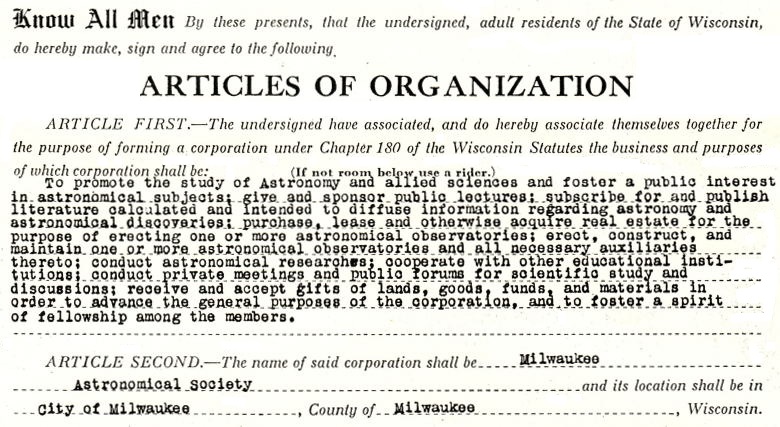

In March of that year, the MAS filed papers of incorporation with State of Wisconsin and became a non-profit organization. This was now a necessity for the club to take possession of the land offer for the observatory.

By October, the 13-inch telescope had been hastily completed and put into use in Armfield's back yard, which was the unofficial location of the MAS Observatory. The mirror box was made out of wood (to be upgraded later), and there was no clock drive. Again, to be added later. But the telescope performed beautifully and even from West Allis, the scope could easily detect a 15.8 magnitude star.

You can get a more detailed account of this telescope in the October, 1934 issue of the MAS Bulletin written by Luverne Armfield here.

You can get read the entire history of this telescope here.

By the end of 1934, the dues were increased to $3.00

($56 in current value).

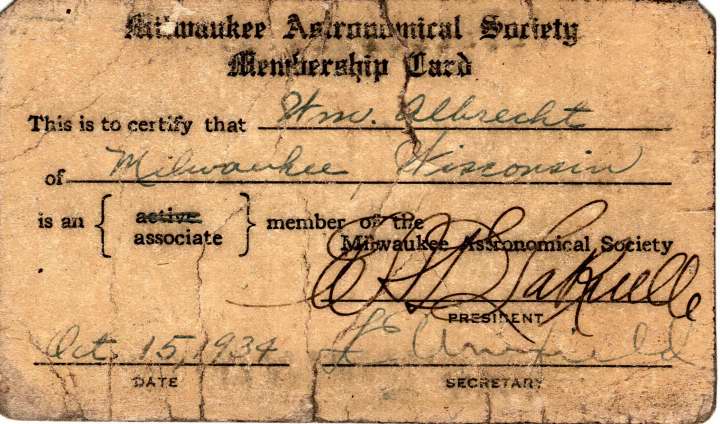

In December, President E. A. De La Ruelle died.

By the end of 1934, the dues were increased to $3.00

($56 in current value).

In December, President E. A. De La Ruelle died.

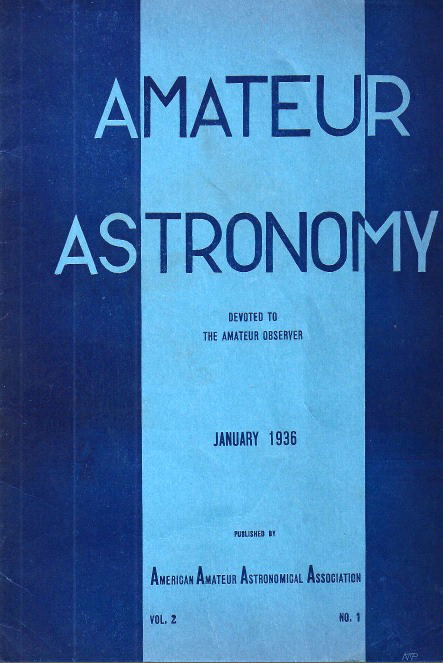

Twin highlights of 1935 were the visit of Dr. Harlow Shapley to Armfield's house (Shapley spoke on Nova Herculis), and the formation of the American Amateur Astronomical Association (AAAA), a joint idea of Armfield's and J. Wesley Simpson. Simpson was the editor of Astronomical Discourse, the publication of the Missouri-Southern Illinois Observers.

Every other month the AAAA published Amateur Astronomy as a journal of the member club activities. The MAS Bulletin stopped publication and instead was incorporated in the AAAA journal. It would be published until 1938 and you can read the issues on the MAS website here.

Coordinated Meteor Observing

The most important impetus for the formation of the AAAA was the value of doing duplicate meteor observations. Meteor observing was one important way that amateurs could contribute to science, and Armfield was an advocate and an observer. Doing meteor counts and establishing radiant points had long been the way amateurs could contribute, but if you could get a good enough plot for a meteor seen by two observers 25-125 miles apart, a parallax could be calculated and, hence, a height calculation could be made.

On its surface it sounds very simple. However, in practice it proved extremely difficult to almost impossible. First, it was difficult to get the decent plot accuracy. It took an experienced observer and that person had to be looking at the right part of the sky. The closer that observer was looking to where the meteor appeared, the more accurate the plot. Second, the odds of another qualified observer seeing the same meteor to make a duplicate plot with the necessary precision were extremely low. Third, just looking at the plots and times it wasn't always certain the two meteor plots were in fact the same meteor! The time had to be very precisely noted and in that era having the necessary accuracy was difficult.

Doing coordinated meteor watching helped to overcome these issues. Rather than two random observers being paired after the fact, the meteor observations would be coordinated so that observers could agree on when and where to look. But even better would be real-time coordination so there would be no question that they were observing the same meteor. In theory it could be done with a phone call, but that would have proven too expensive. So they latched on to the idea of using short-wave radio which was accomplished by teaming up with HAM radio enthusiasts.

It helped solve the various problems. 1) Precision of the plots was elevated by the observers agreeing on where they should be looking. And if it was desirable to change that location, they could immediately agree. 2) You were guaranteed that the other observer was equally qualified. 3) There was no doubt that the two observers had just seen the same meteor. In this case precise timing was not actually needed.

Because the optimal distances for these duplicate observations fell between 25 and 125 miles, teaming up with other astronomy clubs became a necessity and that is where the concept of the AAAA became so important. Read Ed Halbach's AAAA article about the duplicate meteor observation program here.