History of the Milwaukee Astronomical Society

1938: Observatory Dedication

On March 25, 1938, the property was officially deeded to the MAS, having satisfied the requirement of construction. In May, the refurbished 13-inch telescope was installed on the pier.

On June 18th, the observatory was officially dedicated and over 100 members and guests came to the event, many of them from Chicago, Madison, and other outside areas. There was a picnic dinner and when it was finally dark enough for slides to be seen, Ed Halbach, who was President at the time, presided over the event. M. J. W. Phillips made the dedicatory address which included a brief history of the building, illustrated by lantern slides of the various stages of construction. The main address was by Charles Hetzer of the Yerkes Observatory. As the sky was clear, the rest of the evening was taken up observing with the 13 inch scope in the building and many other instruments belonging to the members which were scattered about the grounds.

Cornelius M. Prinslow was appointed the first Observatory Director, responsible for distributing keys to the observatory staff members and running the observatory properly. But the observatory wasn't nearly done. For the next 3 years there would much more added to the observatory to maximize its functionality.

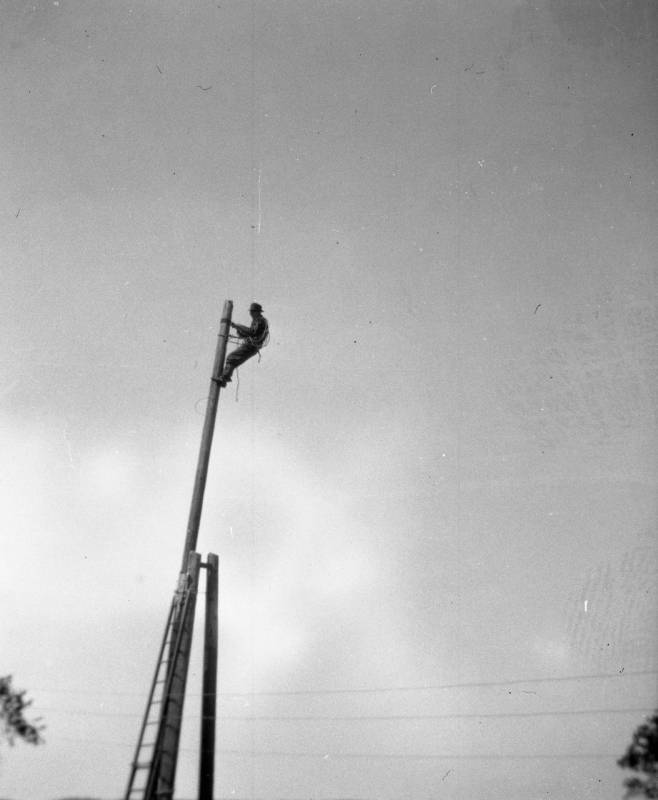

Shortly after the dedication, a 250 watt radio transmitter was installed to coordinate the group's duplicate meteor observations. For the antennae, the plan was to construct two 80 foot towers (which would look like flag poles) with a wire strung between the two. In the picture above taken in the summer of '38 you can see the north tower which was erected on August 27th. The south tower is lying on the ground. They got that pole painted, but it would be the following year until it was erected. Click here to see the same photo which was printed as a large poster that hung at the observatory or at the hobby shows. The lines were drawn on that photo to show the final plan. Because the lines are hard to see, the radio transmitter line is enhanced in yellow while the power line is enhanced in magenta. The project was completed by 1940 and the south tower only appears in one archive photograph because few pictures of the observatory have the camera pointed to the south. However, when WWII broke out in December of 1941, the transmitter was turned off for the duration of the war and that effectively killed the program of coordinated meteor observing.

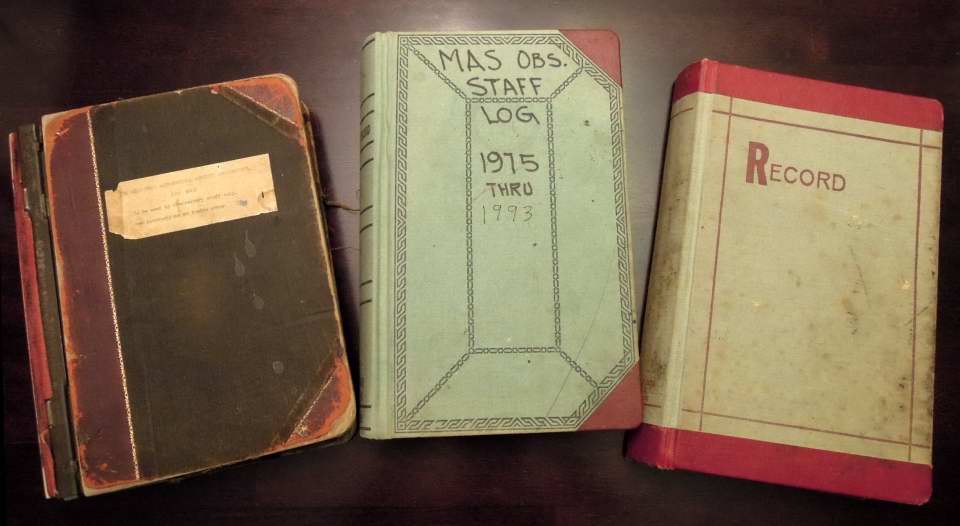

On July 5th, Observatory Director Prinslow instituted a

log book for activities at the observatory. Members and guests were to be logged as well

as observing activities, especially variable stars. And notes about any equipment trouble so they could be addressed.

To this day we utilize a log book at the observatory.

You can read the

actual entries in the log books which have been scanned.

On July 5th, Observatory Director Prinslow instituted a

log book for activities at the observatory. Members and guests were to be logged as well

as observing activities, especially variable stars. And notes about any equipment trouble so they could be addressed.

To this day we utilize a log book at the observatory.

You can read the

actual entries in the log books which have been scanned.

The above aerial photo shows the grounds taken on Sept. 24th, 1938 and we call it our "Field of Dreams" shot because it shows that our observatory was built in the middle of a corn field. The photo was taken by Ed Halbach. We believe the pilot was Ray Ball or possibly his son, John Ball, as they were also in the plane.

The publication of Amateur Astronomy was terminated due to insufficient finances. Without it the AAAA collapsed soon after.

In 1938 and continuing until the end of 1941 with the outbreak of World War II, almost every Saturday during the warmer seasons there was a work party for maintenance and new construction.

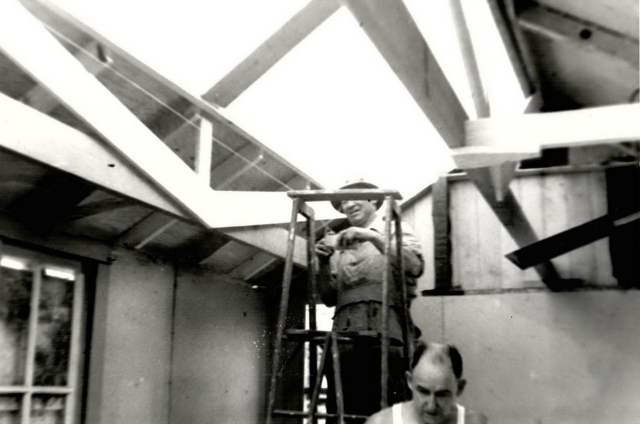

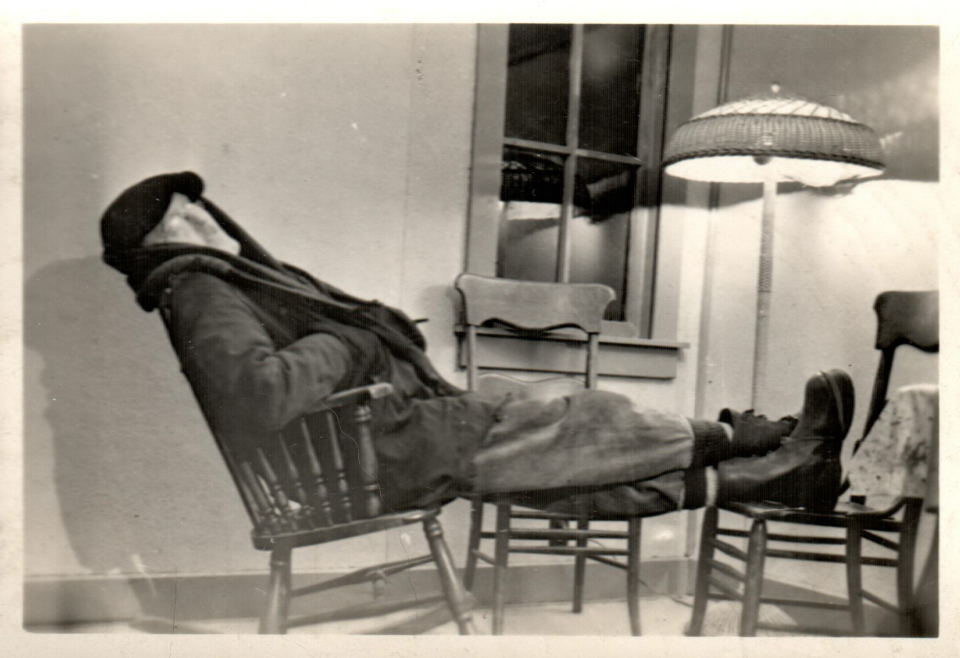

Late in 1938, the society acquired a voting booth building. It was arranged

through the Election Commission and transferred to the Milwaukee Public

Museum. The museum then loaned it, on an indefinite basis,

to the MAS with

the understanding it was returnable on demand, but that as long as we

continued to use it, and carry on a program of public education without

charge to visitors, it was ours. The structure served as an office as well as sleeping quarters

for one shift of observers while another shift used the telescopes. Cornelius Prinslow, the first Observatory Director, is in

the picture at the right. Though it was

initially called the clubhouse, it generally became known as the monastery. Such dedication was not without its

hazards: Ed Halbach dozed off while driving home after one late session and smashed into a light pole, injuring his leg.

to the MAS with

the understanding it was returnable on demand, but that as long as we

continued to use it, and carry on a program of public education without

charge to visitors, it was ours. The structure served as an office as well as sleeping quarters

for one shift of observers while another shift used the telescopes. Cornelius Prinslow, the first Observatory Director, is in

the picture at the right. Though it was

initially called the clubhouse, it generally became known as the monastery. Such dedication was not without its

hazards: Ed Halbach dozed off while driving home after one late session and smashed into a light pole, injuring his leg.

The building was hauled out in early December and quickly assembled the same day. A stove was added the next day to supply heat. Finally, electric was added by stringing a line over to the A-Dome.

1939-1945: Growth and the War

In 1939, the south radio mast was erected near the southeast corner of the property and the line from the north tower was strung to the south. That year, the radio transmitter was finally operated from the observatory to Beaver Dam for doing duplicate meteor plots for height calculations.

More work was needed on the clubhouse and in late May work began to add a short wall around the complete structure to keep out critters and cold air from coming from underneath. In September work began to lay a wood floor in the A-Dome. A concrete foundation was added to the observatory and blocks were added to the building. Then a wooden floor was added. The project was complete by the end of October.

In early February of 1940 a large safe was brought out and put in the first floor of the observatory. It would serve as a safe place to store important documents and smaller equipment like eyepieces.

On the nights of February 24th and 25th, photos were taken of the Great Conjunction which beside Jupiter and Saturn included Mercury, Venus, Mars, and Uranus. The story of one of the photographs can be read here.

This is a rare view of the observatory taken from the northwest in 1940. What looks like a debris pile between the radio mast and the Monastery / Club House are the sections for what will become the tool shed the following year.

On April 20th, work begins on the concrete mount for the Patrol Camera. They start by digging a 6 foot hole and then dug a trench from the the 10-inch pier (that will one day be the B-Scope pier) to the Patrol Camera and two other locations. Finally, after more digging the depth was 8 feet. When the wiring is done, a form is made for pouring the concrete. On May 26th the form is removed.

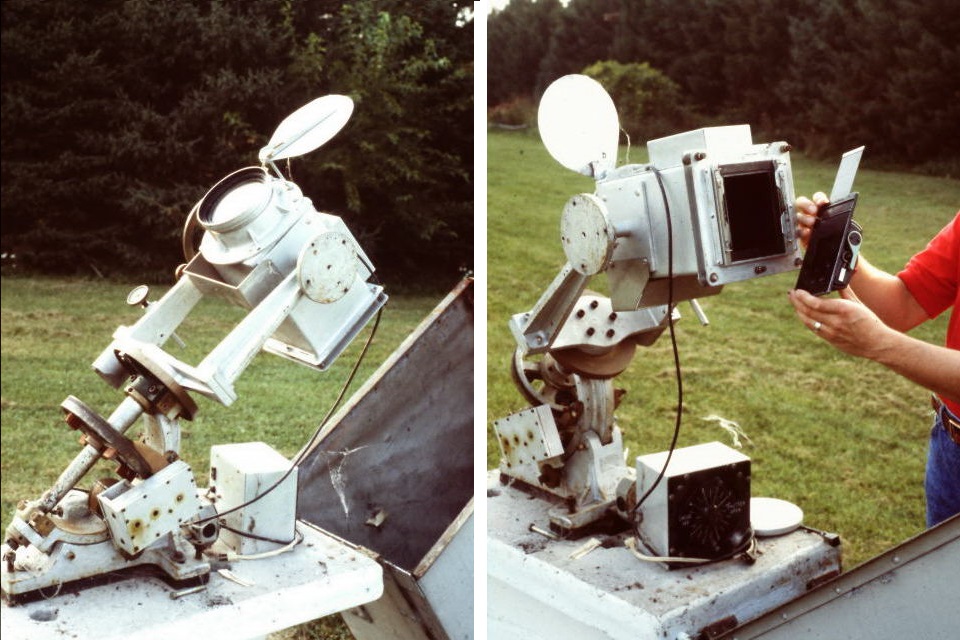

Early in 1940, Harvard College donated a Patrol Camera and will require it be mounted on a concrete pedestal.

Above is the view of the observatory in early May of 1940 with the newly erected clubhouse / monastery before the rebuild. It is one of the few pictures we have that show the outhouse which is seen on the far left of the photo. Most of the expansive photos of the observatory have it cropped out of the picture. Between the outhouse and the north radio mast is a pile of cinder blocks which will be used for the workshop to be built underneath the clubhouse. In this picture you see the construction of the concrete pedestal for the Patrol Camera which was donated by Harvard College. that year. It will be fitted with a metal flip-top.

Also in 1940, the National Geographic Society gave the MAS two Kodak f/2 cameras for aurora photography. Hundreds of photographs of aurora were obtained with these cameras.

View of the grounds in mid-1940. The patrol camera is in the foreground at the left. Comically, over the years many would mistake this structure as a entrance to an underground area.

Starting on August 10th, work begins on the clubhouse rebuild. The structure is partially disassembled so they could build a subterranean workshop.

It is not known how much of the clubhouse was removed and if any machinery helped with the removal of the dirt. The entries in the log book simply list many people helping. A new foundation was laid and presumably the pile of cinder blocks by the north radio mast was used for the walls. It is unknown how the access to the basement worked, but we assume there was initially just a ladder and the following year stairs were added.

In mid-1940, the MAS obtained the first of several donations by the Milwaukee Journal of aging sub station buildings with the goal of getting enough good sections for a complete building. The last one was sitting at 645 E. Otjen Street in Bay View, Milwaukee. On April 20, 1941, MAS members transported the structure to the observatory where it with the previous sections was reassembled. It was an all metal building that was then used as a tool shed. Technically, the building was off the property, but it was on the land of the Phillips Farm and it was allowed. [Note: When the MAS received a donation of 2 additional acres from Harry Phillips (the brother of Matthew) in 1963, it would include the land where the tool shed sits.] Eventually the door will be replaced with a standard garage door so larger equipment could be stored.

Above: one of only 3 known pictures of the interior of the clubhouse / monastery. It shows one corner. The above rack positions hold the AAVSO blueprint charts of variable stars to be observed by the MAS, while those below hold the clipboards of individual observers. The book at the lower right is the log book, which everyone would sign when visiting the observatory, a practice that exists to this very day. The telephone connects with a like instrument in the 2nd floor of the A-Dome.

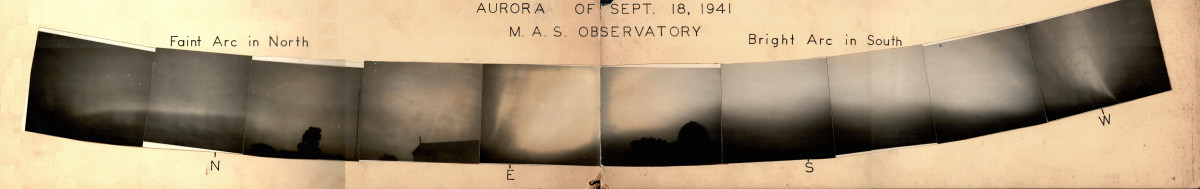

On September 18th of 1941, there was a spectacular aurora display seen at the observatory. Ed Halbach took 80 pictures of the event and this photo collage of 10 of those images were assembled into this panorama. In the sky you can clearly see the Big Dipper just west of north, Capella to the right of the tree in the NE, Perseus, and the Pleiades just above the clubhouse. In the south (photo 8) you can see the teapot part of Sagittarius, and in the west (photo 10) you can see Corona Borealis and Boötes, with Arcturus just above the horizon.

But from a club history point of view, the most amazing item is the radio antennae. At the very right of photo 3 you can see the North Tower and then in photo 4 the wire heading to the south with a guy wire to the ground. From there the wire arcs down and goes behind the A-Dome in photo 6. At the very right you that photo you can see the South Tower. That tower was the same height as the north one, but more distant as seen in the photo. This is the only known photo of the completed South Tower. There is no mention of the tower being erected or being taken down, but there are pictures of the tower erection shown earlier. And, sadly, the meteor height calculation program that utilized short-wave radio was shutdown in less than 2 months with the outbreak of World War II.

The observatory as it looked by the end of 1941. The Tool Shed is at the far left. The exact date of the photo is unknown, but it was probably around 1947.

In 1942, Ed Halbach became the second Observatory Director, a position that he will hold for the next 35 years. But in 1942, with the onset of World War II, between members serving in the military and gasoline rationing, observatory activities slowed to a crawl. In an effort to get additional gas rations, Halbach and Armfield set up an optic shop, making roof prisms for the war effort. Matthew J. W. Phillips (who donated the observatory site) passed away on June 2, 1944. By the end of 1944, the optical shop failed and Armfield then took a job with the Telephone Company of Indiana and Michigan, moving to Ohio.

Gas rationing would end in 1945 when the Japanese surrendered. The MAS conducted an expedition funded by the National Geographic to Pine River, Manitoba, to tie the North American grid maps to the European grid maps. The expedition is successful.

In 1945, Ralph Buckstaff, a long time member living in Oshkosh with his own private observatory, announces that he will donate his 12-inch reflector to the observatory as soon as he completes his new 16-inch reflector.