Sputnik 4 and the MAS

By Gene Hanson

International Geophysical Year

The International Geophysical Year (IGY) was an international scientific project that lasted from July 1, 1957 to December 31, 1958. It encompassed 11 Earth sciences: aurora and airglow, cosmic rays, geomagnetism, gravity, ionospheric physics, longitude and latitude determinations (precision mapping), meteorology, oceanography, seismology, and solar activity. The timing was well suited for studying some of the phonomena as it covered the peak of solar cycle 19. It also marked the end of a long period during the Cold War when scientific interchange between East and West had been seriously interrupted with the ongoing Cold War. Sixty-seven countries participated.

In July of 1955, President Dwight D. Eisenhower's administration announced that the US intended to launch "small Earth circling satellites" between July 1957 and December 1958 as part of the United States contribution to the IGY. Project Vanguard would be managed by the Naval Research Laboratory and used sounding rocket which had the advantage that they were primarily used for non-military scientific experiments. But this was pretty much just a ruse because we were already planning to launch a satellite and it was unclear whether satellites would violate the sovereignty of other nations skies, especially the Soviet Union. But soon after the Soviets announced that they, too, planned to launch a satellite.

Project Moonwatch

Of course, at that time there was no worldwide tracking system to monitor any orbiting satellites and it would take years for its development. Harvard astronomer, Fred Whipple, who was the appointed the director of the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory (SAO) in 1955 proposed that amateur astronomers could be used to help in the efforts to track the early satellites. In 1956 Project Moonwatch was launched by the SAO and then early the following year MAS joined. The Soviets made good on their promise on October 4, 1957 with the successful launch of Sputnik which shocked the United States and was the birth of spacerace.

The Milwaukee Astronomical Society was particularly well suited for the moonwatch program as the club was heavily involved in meteor observations

since the very beginning of the club in 1932 and especially because of the upcoming maximum of the Leonid Meteor Shower of 1933. And then a few years

later the club

were pioneers in doing duplicate meteor observations with observers ideally stationed 25 to 125 miles apart coordinated by short-wave radio. When the same

meteor was observed at the different locations the paths were

plotted on a star atlas which allowed them to get a parallax and therefore get a height calculation of the meteors. When news of the launch of Sputnik 1

became known, the MAS independently first caught and recorded the radio signals from the craft, and then actually saw both the 2nd stage rocket (which was very

bright and easily seen) and then the satellite itself (which was dim and needed optical aid to see).

The Milwaukee Astronomical Society was particularly well suited for the moonwatch program as the club was heavily involved in meteor observations

since the very beginning of the club in 1932 and especially because of the upcoming maximum of the Leonid Meteor Shower of 1933. And then a few years

later the club

were pioneers in doing duplicate meteor observations with observers ideally stationed 25 to 125 miles apart coordinated by short-wave radio. When the same

meteor was observed at the different locations the paths were

plotted on a star atlas which allowed them to get a parallax and therefore get a height calculation of the meteors. When news of the launch of Sputnik 1

became known, the MAS independently first caught and recorded the radio signals from the craft, and then actually saw both the 2nd stage rocket (which was very

bright and easily seen) and then the satellite itself (which was dim and needed optical aid to see).

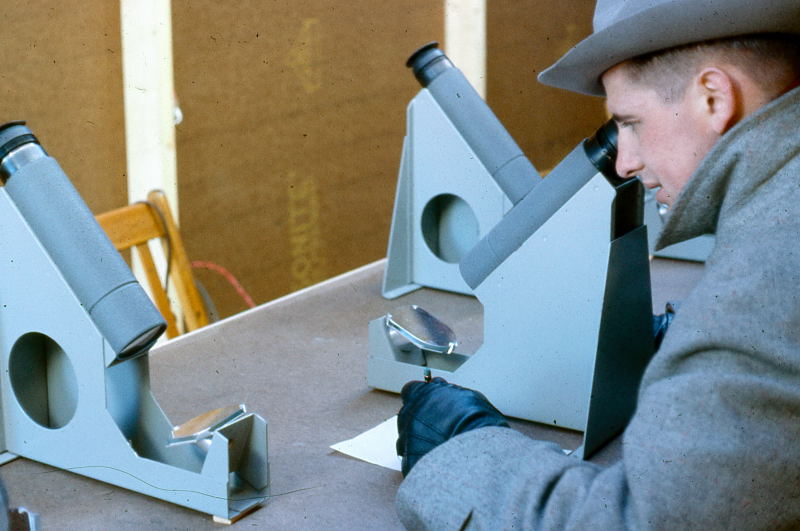

The basic telescopes for the work were somewhat unique in that the scope itself pointed fixed and down at about a 45° angle to provide a comfortable

viewing position for hours. It was pointed at a mirror which was moved to change the position in the sky. The MAS quickly built a structure that would

hold 12 observing positions. The structure, of course, was not necessary, but it provided protection from the wind during cold winter evenings.

The basic telescopes for the work were somewhat unique in that the scope itself pointed fixed and down at about a 45° angle to provide a comfortable

viewing position for hours. It was pointed at a mirror which was moved to change the position in the sky. The MAS quickly built a structure that would

hold 12 observing positions. The structure, of course, was not necessary, but it provided protection from the wind during cold winter evenings.

The observations were reported to the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory (SAO) which provided a star atlas (basically the Bonner Durchmusterung) for positioning and plotting.

Korabl-Sputnik 1 - AKA Sputnik 4

The United States took months to respond with its own successful launch, and the Soviets would go on to

launch more satellites including 3 that went to the moon. Then the Soviets began concentrating on putting a man in space.

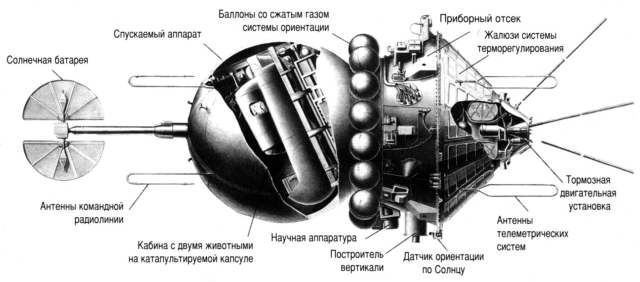

The 4th orbital mission was

Korabl-Sputnik 1,

but in the west it was known as Sputnik 4. It was a 5-ton vehicle and a test to first put animals and then humans in space.

Launched on May 15, 1960

and intending it to land back to Earth safely after 4 days, the mission

would encounter a problem leaving it in a derelict orbit until it finally fell in

Wisconsin on September 5, 1962.

The United States took months to respond with its own successful launch, and the Soviets would go on to

launch more satellites including 3 that went to the moon. Then the Soviets began concentrating on putting a man in space.

The 4th orbital mission was

Korabl-Sputnik 1,

but in the west it was known as Sputnik 4. It was a 5-ton vehicle and a test to first put animals and then humans in space.

Launched on May 15, 1960

and intending it to land back to Earth safely after 4 days, the mission

would encounter a problem leaving it in a derelict orbit until it finally fell in

Wisconsin on September 5, 1962.

A Shift in Focus

After only a few years the Moonwatch program was waning as automated systems had taken over. But around 1962 Fred Whipple who headed the program turned the focus to sighting a satellite reentry and then recovering any fragments that survived. This would be difficult because much of the satellite would burn up in reentry. Also, 4/5ths of the Earth's surface is water. Of the 1/5th which is land a large portion at the time was behind the iron curtain. And within the free world the majority of the land is uninhabited, forested, mountainous, etc. On top of all that the reentry would have to be observed, point of impact calculated, and then any fragments located. A successful recovery would be valuable in the field of radiation because the time the fragment was in space would be precisely known. Though they had recovered some fragments, they were all only in orbit for a few days so would need a fragment that had been in orbit for a lot longer.

But there was even more difficulty. Though they had precisely calculated orbits of the satellites, those predictions got less and less reliable as the satellite got too low with the drag from the Earth's atmosphere slowing the orbit speed.

An Opportunity for the MAS

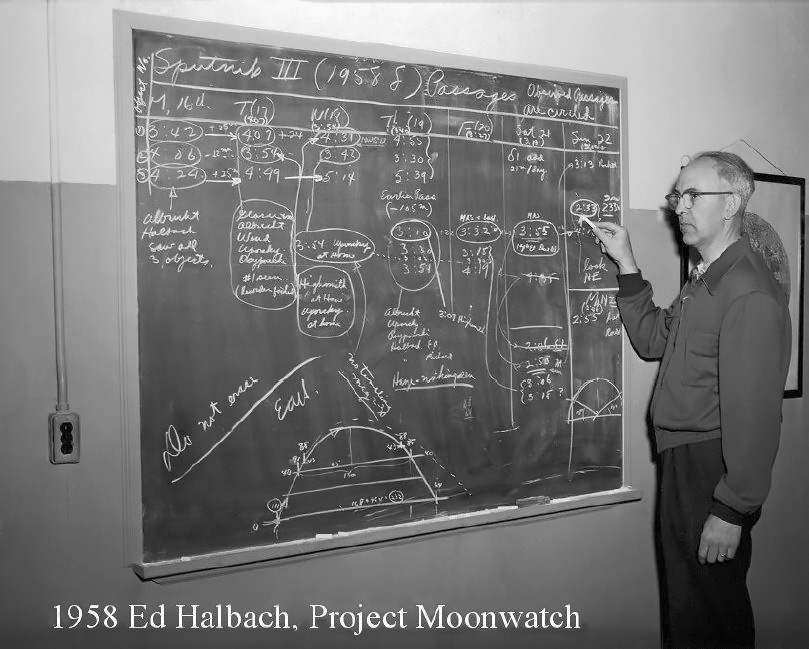

An opportunity presented itself with Sputnik 4 as the predicted reentry was on or about Sept. 6th, 1962. Moonwatch prepared a prediction emphemeris showing the times the satellite would be above the various Moonwatch stations. With Sept. 6th being the prime target, watches needed to take place from Sept. 5th thru Sept. 7th.

On the night of September 4th, Moonwatch team leader Ed Halbach and Gale Highsmith held a training session at the MAS Observatory to prepare the team for reentry patrol. The ephemeris showed that the orbital plane of Sputnik 4 would be over Milwaukee at 8:25PM that night. The team waited, but clouds interfered and it didn't clear until after the predicted time. The team didn't see anything.

MAS members Ray Zit and Leonard Schaefer planned to be back at the observatory by 4:00am for another orbital pass predicted at 4:58am. Gale Highsmith would observe near his home in downtown Milwaukee.

By 4:00am, 58 minutes before the predicted zenith time, Highsmight had his homemade theodolite set up. At 4:39 he noticed what at first appeared to be a reddish-orange starlike object low in the northwest. The object then appeared to separate into many pieces. By the time he was able to get the first fix (Azimuth 340°, altitude 8°), six pieces were distinguishable all moving SE, glowing at an estimated -6 magnitude before fading rapidly to extinction. The time was 09:49:47UT (Sept. 5, 1962) recorded with a stopwatch and later compared to a WWV time signal, when the leading and largest object was at an azimuth of true north and an altitude of 12°. By this time only the leading object was still visible. It was followed out over Lake Michigan to an azimuth of 16° and an altitude of 11°, at which point it ceased to be visible.

At the MAS observatory Zit and Schaefer started their session at 3:45AM and then witnessed the reentry, noting the time of 4:49am with the brightest object at magnitude -4.5 (the brightness of Venus at maximum). They did not get any altitude/azimuth measurements, but were able to plot the movement against the background stars on a chart. Many other early risers got to see it as well. Most witnesses reported seeing up to 24 pieces and some reported a "thunderlike noise." However, no one reported seeing any fragment hit the ground. But it was clear that the main sections of the satellite fell in Lake Michigan.

Within minutes the Milwaukee Journal and local radio and TV stations reported the event and that pieces of the satellite might be found in the area. Residents finding suspicious pieces of metal were asked to rush them to the Journal. The result as you would expect was a strange assortment of just plain junk.

A Mysterious Object in Manitowoc

In Manitowoc that morning, unaware of what had been seen in other parts of Wisconsin, patrolmen Ronald Rusboldt and Marvin Bausch were cruising the streets in their squad car. At 5:30am they noticed in the middle of the street a small object resembling an irregularly shaped piece of cardboard. When they passed again at around 7:00am, they saw the object was definitely metallic, so they stopped to remove it as a hazard. They were surprised to find the object imbedded in the asphalt and too hot to handle, but managed to move it to the side of the street. It remained there until the afternoon when the same patrolmen, having heard the news reports, went back to take another look. The object was still lying by the curb, so they took it to police headquarters. Personnel from two local foundries and a shipward were called in to inspect the object, but could not identify it. They asked a visiting salesman, Kenneth Gevers, who was on his way to Milwaukee to drop it off at the Milwaukee Journal.

Halbach Does His Own Analysis and Makes Replicas

Upon receiving the object, the Journal notified Ed Halbach of the Manitowoc discovery, and he quickly called Moonwatch headquarters at SAO and took the piece to his house in Milwaukee where it mostly laid on his kitchen table, according to 3 of his daughters who were obviously eyewitnesses. They also said, "He made four casts of it! He used a cement pillar form to make the mold."

At this time it wasn't an absolute certainty that this piece was from the satellite or even something from space, although the timing was perfect. Again, according to his daughter, Halbach thought it must be from Russian because the measurements were in even metric units.

Highsmith Goes to SAO Headquarters

Reentry observer Highsmith was commissioned to fly the object to Cambridge, MA, as the local examination by Halbach had not ruled out the possibility this piece of metal was indeed a satellight fragment. Highsmith arrived in Cambridge on Thursday afteroon, Sept. 6th. Dr. Charles A. Lundquist, SAO's Assistant Director and a group of SOA people were there to meet him.

The object was laid on a table in Lundquist's office for the group to see. They could tell the blackened hunk of metal was obviously manmade, but it appeared to be solid steel and far thicker than ordinarily used in satellite construction. On the other hand, it appeared to have been subjected to great heat and a considerable amount of melting.

Hoax, Junk, or Real?

The initial reaction, according to Dr. Lundquist, was one of "skepticism that the fragment was authentic." The whole atmosphere was one of "amusement and curiosity." The first step was to photograph the object from every angle. Then careful measurements were taken - still in Lundquist's office. Suddenly hopes began to mount. All measurements figured out in the metric system, a system not used by American manufacturers but used throughout Europe including Russia.

The object was crudely disk-shaped, approximately 20 centimeters in diameter and 8 centimeters high. It weighed 9.49 kilograms or about 20 pounds, and the top cylinder plate precisely 1 centimeter thick.

The SAO scientists then took the object downstairs to their machine shop and cut a pie-shaped section from it. Luck was with them. The cut exposed an embedded bolt in an irregular layer of metal that had melted and resolidified. The threads on the bolt were measured: 1 thread per millimeter - again, the standard European size. Dr. Lundquist said, "We then knew that if this was a piece of junk, it was a strange piece to be found on a Wisconsin street." His initial conclusion was that the fragment was "probably authentic," and was convinced enough to then call the Director of NASA's Office of International Programs to give him as much lead time as possible with regard to international implications of the recovery.

Conclusion

The final proof, however, was that the object had been exposed to the radiations of space. It would take the next 2 days. By melting down a fragment of the object to release radioactive gaseous isotopes that might have formed and been trapped in the metal. They found traces of Argon 37 and Manganese 54 which could have only been formed by sustained bombardment by cosmic rays and trapped particles in the Van Allen belts. The object was therefore deemed a genuine part of Sputnik 4.

Meanwhile Back in Wisconsin

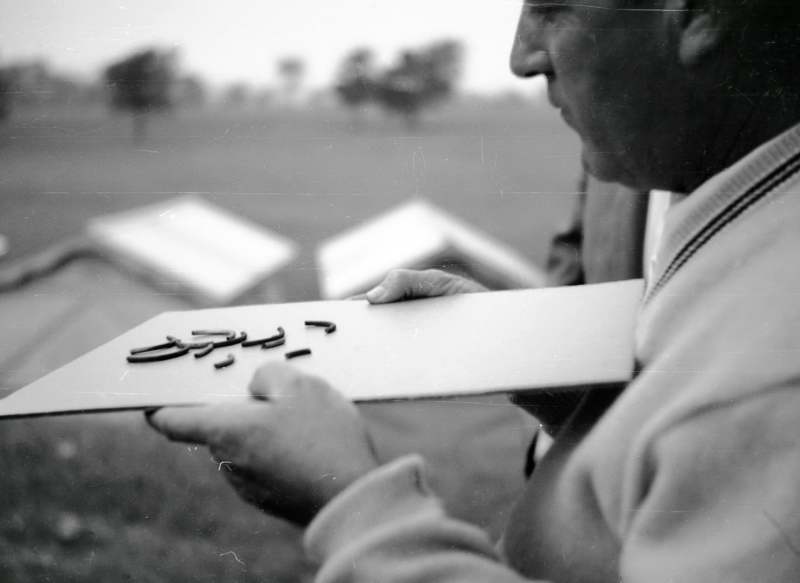

But the MAS wasn't done with Sputnik 4. Headed by Ed Halbach, they were busy screening observation reports and specimens. It soon became apparent that the eye-witnesses rarely understood what they saw, and often their descriptions were grossly in error. For weeks after the reentry event, the Moonwatch team and other interested individuals spent many hours of their own time trying to learn as much as they code about the reentry ground path and the authenticity of purported fragments.

Obviously, the team would very quickly head to Manitowoc to visit the site of the 20 pound fragment and then visit other sites where fragments might be found and verified. The large fragment fell in the middle of North 8th street near the intersection with Park St, directly in front of the Rahr-West Art Museum.

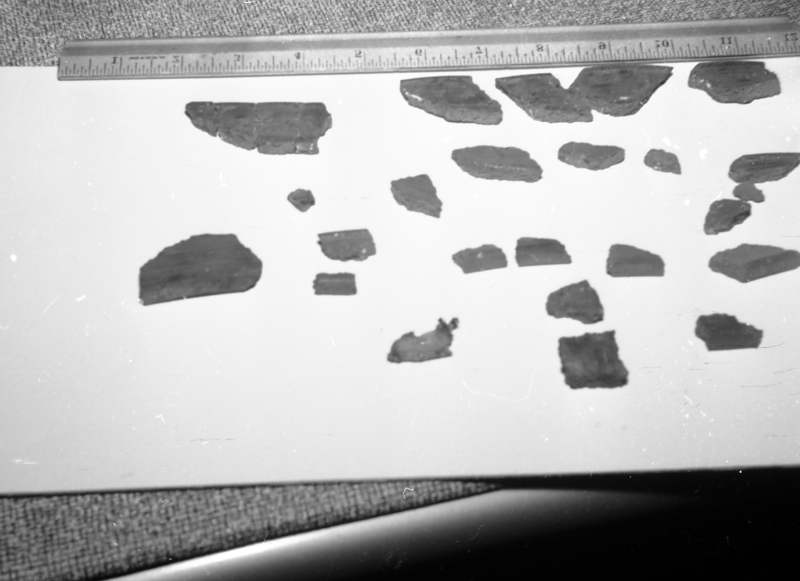

These pieces and this documentation were donated to the MAS by T. E. Williams son, Tom in 2014.

Legacy

It would take some time for Manitowoc to embrace what had happened. The following year in November, the International Association of Machinists embedded a brass ring in 8th Street to mark the exact spot where the Sputnik fragment had fallen. Then sometime later a small slab of granite was mounted at the side of the road, directly parallel with the brass ring. (See the photos that follow.)

The 20 pound Sputnik fragment that fell on 8th Street which happened to be right in front of the Rahr-West Art Museum. They have

one rather unusual piece that's decidely not art: a display case for one of the replicas that were produced by Ed Halbach. The description clearly says it fell

on September 5th (which is correct) versus the granite monument on the sidewalk that says September 6th.

The 20 pound Sputnik fragment that fell on 8th Street which happened to be right in front of the Rahr-West Art Museum. They have

one rather unusual piece that's decidely not art: a display case for one of the replicas that were produced by Ed Halbach. The description clearly says it fell

on September 5th (which is correct) versus the granite monument on the sidewalk that says September 6th.

Sputnik 4's biggest legacy is Sputnikfest. This celebration began in 2008 when a few members of the Rahr West Art Museum decided they wanted to put on an event for the historical artifact. They thought it would just be one year and that it would be a bust, with hardly anyone showing up, frankly thinking it was a stupid idea. But over 3000 people showed up! So this started a yearly event run by Rahr-West Museum taking place on 8th Street.

Some Notes By the Author

I originally wrote this article back in 2014 when Tom Williams contacted the MAS the he wished to donate the Sputnik 4 spring fragments found by his father on a golf course in West Bend along with the document prepared by Ed Halbach. When I first started visiting the MAS Observatory as a 13 year old I vividly remember seeing the 20 pound piece of Sputnik 4 in a display case in the Quonset Hut meeting room. But, frankly, I wasn't all that impressed because it said it was just a replica. But many years later I had a different impression when I learned the back story of how the MAS was instrumental in its recovery.

The story I read about the piece was that before the original fragment was returned to the USSR, NASA made 2 replicas which both ended up in Manitowoc, one at the Rehr-West Art Museum and the other in either the Manitowoc's Safety Building or the Manitowoc Area Visitor & Convention Bureau. But there had to be more to the story because clearly the MAS had a replica so the count was 3. To me it made sense that we'd be the recipient of one of these because of the pivotal role of the MAS.

Then I got a much clearer and more complete picture of the events by the children of Ed Halbach. I was contacted by Betsy Halbach Rockwell in 2021 that the family was in possession of another replica which was given to one of Ed's granddaughters. That meant there were now 4 known replicas! She also said members of the family intended to go to Sputnikfest the following year (2022) because it would be the 60th anniversary of the fall. In a followup email she included her sisters and brother, I learned from Richard that the large piece wound up in the Halbach home and Ed by measuring a visible bolt fragment that indeed this was of Soviet origin as the pitch appeared to be metric.

As a sidelight Betsy wrote, "I believe all of my siblings will be visiting the Racine area this Labor Day to celebrate my sister Mary's September 5th birthday. Her 12th birthday celebration in 1962 was upstaged by Sputnik."

Betsy Halbach Rockwell, Mary Halbach Nordlie and Joanne Halbach Moore at Sputnikfest 2022 to celebrate the 60th anniversary of Sputnik to honor their father, Edward A. Halbach. The shirts they're wearing were made by Joanne and are hilareous!

The photo is by Martha Hayden, used by permission. Read her account of attending the 2022 Sputnikfest and meeting the Halbach daugthers here.

But the daughters had another sort of bombshell. Not only had the large fragment been in their house and on their kitchen table, according to Betsy, "He made four casts of it! He used a cement pillar form to make the mold." Having done a lot more research this story is very credible because NASA could not have produced a full replica. Within an hour of arrival of the 20 pound fragment at SAO Headquarters, they had cut a pie-shaped section from it. Later another fragment was melted down for the radioactivity measurements, the final proof that the object had not only come from space, but the time exposed to the radiation matched the orbit duration.

Photos: Slides and Negatives

In 2023 I was contacted by another daughter of Ed Halbach, Kathyrn. She had many slides that she inherited from her father and wished to send them to the MAS and needed an address. Of course, as the club historian I gave her my address and a week later I received an assortment of 35mm slides and negatives. Within the collection of slides were pictures of the MAS Moonwatch program. I had nothing in the photo archive about Moonwatch other than a single picture of Ed at the blackboard seen above. Then there were two rolls of negatives all of which were from September of 1962! The slides and negatives are identified above with "MAS Photo by Ed Halbach."

Other MAS Historical Notes

The following entries are from the MAS archives citing newspaper articles and one magazine reference.

The actual clippings are missing.

Magazine clipping: "...hot-rolled carbon steel heated to or near melting

...a melted steel aglomerate on a fragment covered with white

powder, containing large amounts of magnesium oxide..."

Newspaper clippings:

9-5-62 Sputnik IV launched in May, 1960. Tracking revealed change to

higher orbit several days after launch and predicted its fall

so observers were watching. Halbach asked for sightings of

fragments.

9-7-62 Photos from Manitowoc- Smithsonian Astrophysical scientists

analysing 20 pound disk of metal. (incomplete article)

9-6-62 Kenneth Gevers (steel salesman) brought 20 lb. chunk to

Milwaukee (the one we have - a replica), sent it on its way to Smithsonian

Astrophysical with Highsmith on advise of Halbach and Highsmith.

Hole in street had ground stones in bottom as if object had

been spinning.

9-8-62 Whipple (S.A.) spokesman - tests not yet conclusive. Smithsonian

reps critical of Highsmith's casual transporting and asked if

he had been followed. 10 more found fragments sent to NASA.

9-10-62 Spring-like fragments found in West Bend. Halbach said pieces

might be part of rocket nozzle rim. Confusion over who should

take charge of found pieces and where to send them.

9-8-88 Photo Joseph Wisner who saw breakup kneeling next to plaque

at 8th and Park in Manitowoc. Definitely identified, according

to article, as Sputnik IV with 20x8 centimeter (20 lb.) piece.

Part of fragment sent to USSR - another part kept by NASA.

NASA made 2 replicas - one on display at Manitowoc Police Dept.

the other inside Rahr-West Museum.

Sources of information in this article

Sputnik IV Re-entry: The Role of Moonwatch

The Death of Sputnik IV: Mainstreet, U.S.A.